What do you really need?

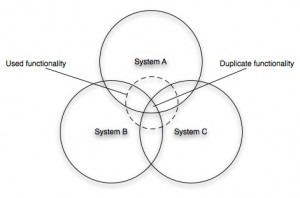

A couple of clients I’ve worked with recently have been consolidating their application space, decommissioning old technology and replacing it with a new single application with a core user interface. I’ve written about this before but it is worth revisiting. All too often the starting point is the functionality and the features of the existing applications. The client states we must at the very minimum maintain feature parity, and where the business needs, enhance functionality. Starting with the existing applications and as-is processes is a good start, but never where the focus should lie. The focus should be around the business intent; what are the business goals the system is helping the user achieve? Spending time with the end users of the system is enlightening. It is a crude picture, but this shows what the truth often looks like.

There are three systems that have been developed over the years, commissioned by different business stakeholders with different budgets and different delivery teams. Of each of these systems only a fraction is ever used. (This is especially true of vendor products that have requirements rooted in the market rather than the specific needs of that organization. Think about how many of the features in Microsoft Word you use). If there is significant functional redundancy in the applications, there is also duplicate functionality that results from the different development legacies. It is not unusual in such a landscape for the user to enter the same data into each system. Not something you would wish to replicate in a new world.

In building a new application, the place to start looking for requirements is not so much the as-is processes or existing applications. The place to start is the business intent and what the business actually wants the system to do. More importantly, that means starting with an open mind and challenging notions of process complexity. Is the process complex because it really is, or because the current systems make it that way? In my experience, more often than not, it is because of the former. Spend time with end users, see what they do today. By asking seemingly stupid questions, taking a starting position that the process is simple and challenging ‘why not?’ can yield valuable insights. By all means consider the as-is world, but don’t let it cloud your judgment in designing ‘to-be’.