Let’s assume that you are not bought into the whole agile thing. That doesn’t mean you can’t look at your IT organisation and identify waste and fat in the process. How long does it take from the business having an idea and requesting IT to build something to the developers actually starting to code?

This seems to be common: The initial ‘idea’ is fed into the PMO team, it is documented with a high level scope, rough business case and napkin estimate of +/- 100%. Elapsed time (i.e. the time from the first email or conversation requesting the requirement through to the initial scope document being circulated and approved): two weeks, value added time (i.e. the time actually spent thinking, doing or deciding); two hours. The project, having gained approval in principle, is then prioritised. Some organisations actively monitor thier project protfolio, others do it annually, with the business having to put in project requests when the budgets are set. Mid-cycle and the project is unlikely to take off.

Let’s assume PMO agree the value of the project, next step is high level design. Analysts capture high level requirements, ascertain what the business really wants and refine the business case further. IT puts some high level estimates against the requirements, with a +/- 80% confidence. Elapsed time: eight weeks. Value added time two weeks. With a refined business case to take to PMO or the steering commitee all that has changed now is that we have some more detail and a guess on what it might cost. We are ten weeks down the road and we still have not made a decision whether the project will commence. This due dilligence is notionally about reducing risk and keeping costs in check, but in reality, what value has been added?

Now it is time for detailed design. Another (elapsed time) eight weeks of analysis, drilling down into the requirements. Documentation follows workshops, only now the specification is no longer speaking the language of the business. Use cases, UML, it’s all getting slightly technical and the business are not really sure what they are reviewing. Let’s call it another couple of weeks of actual value that is added.

Eighteen weeks elapsed time, countless meetings, momentum and still no decision on whether project will start, let alone a line of code being written. But the business case is really taking shape and IT have got the estimates down to a 20% confidence limit.

The project gets the go-ahead, but it is not yet time to start coding. Technical design needs to take place, four weeks of architects architecting and documenting the spec. Six months has elapsed (of which maybe a month was actually doing stuff that positively contributed to the success of the delivery) and finally the developers start writing code.

What value did that six months deliver? Requirements, design, business and estimates. Yet we all know that the requirements will change, and with that the business case. The estimates will be way out, but we’ll justify the process of estimation because they would have been right it the requirements hadn’t change during the build…

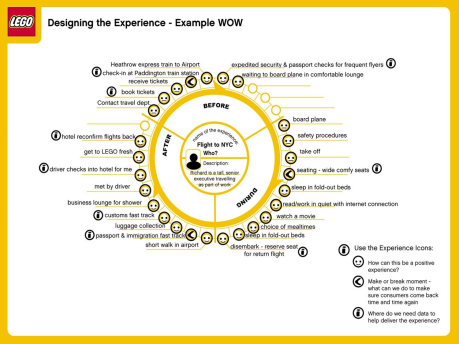

Knocking the process is easy. What’s the alternative? Start with a burning desire to release something of value at the earliest responsible moment. Get the business in the same room as the analysts and the architects and get them to articulate their vision. Use personas and more importantly scenarios and customer journeys to drive out the business vision. Ask the analyst to capture the business intents on index cards. Lots of whiteboarding, visualisation and pictures to inform the thinking. Don’t dwell on the detail, this is about capturing the intent of the system, what are the desired outcomes that it will deliver, how will it impact the lives of all the people who will touch it. Next step is to prioritise these outcomes. Collate these into the minimum set that would make a coherent and compelling product that you could go to market with. For the business case make basic assumptions on the revenue that this feature set will deliver (or what costs it will save) and ask the architects and developers in the room to do some high level estimates. The whole process should take no more than a week (you could get a first cut done in a couple of days) and there is your initial business case. If we accept that estimates are little better than guesses and things will change anyway, if we have an initial realisable goal that we have demonstrated will deliver value, why not go straight into development. By actually ‘doing’ you will minimise risks that you can only predict on paper, and value will be delivered so much quicker, indeed you should be able to have something to market, generating revenue in the same timescales that you otherwise spent planning and analysing. And if you still want to do waterfall, you’ve got a smaller number of requirements to analyse and design for, again, delivering value sooner.