There may be a niche in the market, but is there a market for the niche?

How do you create a successful proposition? If the answer was obvious there wouldn’t be so many failures out there in the market place.

It is easy to commence on a journey of product development with a hunch and clearly there is no substitute for validating ideas in the flesh. That something at ThoughtWorks we do; helping clients test and learn, rapidly building ideas into tangibles that can be piloted at low cost and low risk before investing in significant build and spend. However, sometimes a little more rigour is required before you commit to commencing a project in earnest.

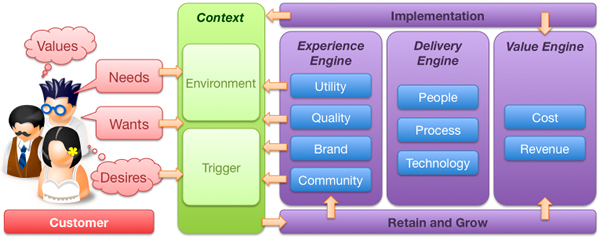

That rigour needs to be focused. What often happens is this rigour turns into a research phase that turns into a project itself. It need not be this way. There are certain things you can do, certain questions to ask as you set out on the journey of creating a new, compelling customer proposition. What follows then is a strawman customer value proposition model to help test potential propositions before moving forward with them. There are three components to the value proposition model; the customer, the environmental context and the organisation or company.

All too often propositions are rooted in the organisation. They make assumptions about the demand or usage. This model attempts to broaden the analysis and focus upon the customer and the why the proposition will be attractive to them. The model supports questions that may be asked to help shape thinking, test hypotheses and validate thinking.

I do not propose that this should become a major research exercise (for example market sizing is a huge effort in itself), rather a tool for asking the right questions, and if the answers are hard to come by, maybe that suggests more thought is required in refining the proposition.

So here goes, a model that provides a framework for considering new customer value propositions. It’s just an initial idea and I’d welcome feedback and suggestions.

Customer

Before you get too carried away with the proposition, a good starting point would be the customer. Who are they and what do they do. Let’s remember that your customer is not everybody. Your proposition in unlikely to be appealing 24/7. The challenge is to segment your target market and identify the triggers for action.

The persona: Who do?

Personas are a useful tool for bringing the customer to life. Much has been written about them, but they are a useful tool for extracting broad data into specific stories that describe individuals. Realise that it is unlikely you will design for everybody. Start with the market that you are targeting, how large is it and what is its propensity to spend? Then within that target market segment the target customer base into different profile customers (personas). You need to understand which persona, which customer profile is most important – prioritise them and focus on the highest value. This may mean deciding between high volume, low margin mass market and low volume, high margin niche appeal. This decision needs to be made as early as possible to ensure the proposition remains focused and doesn’t try to be all things to all people, satisfying none.

Values, needs, wants and desires

People are not empty vessels waiting to consume and be filled with your proposition. Their behaviour is driven by their values, needs, wants and desire. These may be fundamentally rational (to satisfy a basic human goal) or emotional (to demonstrate status). They are cultural and time based. Thinking in these terms helps you understand how the proposition will appeal to the customer at different levels. Let’s take an example of this; a new mobile phone.

Before we think about what the product must do, what are the values that the persona associates with the phone. Is our target market a technophile or a technophobe? Jan Chipchase who works for Nokia includes ethnography in his research to understand how people use their phones; women carry them in their handbags, men in their pockets or their belts.

The basic need that the phone must meet to satisfy the customer, she must be able to make and receive calls. If the product is unable to meet these needs it is not fit for purpose and the phone proposition will inevitably fail.

Just making phone calls meets the need but there are additional wants that should be satisfied for the product to be more compelling. It’s a hassle to remember the number of every person she rings, the customer wants to be able to store numbers and see the number of the person who is calling.

Having the ability to see a photograph of her daughter as a screen saver on her phone is neither a need not a want. The phone is useful and usable without that. But the customer desires to personalise her phone by having a picture of her daughter on it. Desirability is the key differentiator of the iPhone. It doesn’t need to compete on features, it is a cool device that people talk about. And here is a key decision you need to make on your proposition journey. Are you looking to compete on parity or whether you want to make a difference.

Questions

- What is the basic need that the proposition is trying to fulfil?

- What counts as hygiene?

- What does the customer need to be satisfied?

- What does the customer want in addition to being just satisfied

- What do other competive products do to maintain feature parity (if you feel you really need to compete on features alone – bad move!)

- Few people would argue they don’t want simplicity and clarity in their interactions with products. How could your product to make life easier for the customer?

- What will make the customer feel good in themselves about owning the product?

- What other products are “cool” or desirable to your target market. How can you leverage the essence of those products?

Context

So now we are beginning to understand who the customer is, it is time to nest the proposition in terms of their context. The old maxim that a half drunk bottle of water in a desert is worth its weight in gold, but on the streets of a city is worthless trash, should be remembered. Even the best of propositions will deliver little value if they not only consider the customer, but also the context in which they apply: time, demand and usage.

Trigger

So the next step in the model is to ask why, when and how will the customer be attracted to the proposition. What is the trigger that drives the customer to move from awareness (assuming you have that) to action? There is no point in a financial services company trying to sell me a car loan if I am wealthy enough to own my own car, or I do not drive. Understand what triggers the customer to be interested in the proposition, when and why this happens. How can your proposition be at front of mind when the trigger is set.

Questions

- What lifestyle / lifestage events will trigger?

- Internal events personal to the customer; leaving school, getting a first job, getting married, moving house, retiring etc

- External events that they have no control over (think about sports sponsorship and tying a proposition to that sport, or tying a proposition to a celebrity e.g. Michael Jackson..)

Environment

It is very unlikely that the proposition will be wholly unique. What is the competitive landscape, what noise will it need to be heard above to capture the consumers attention. Whilst you may review the immediate competitors to see where threats and opportunities lie, what can you learn from other, unrelated products or domains? How can you fuse together concepts from outside your immediate focus to bring new innovation to your product? Scenario planning may come in useful, playing out different outcomes for different timelines other than that which you plan for.

Questions

- What is the competitive landscape?

- What can you learn about similar but unrelated propositions?

- Have you considered the political, environmental social and technical influences using the old PEST analysis?

- Have you considered different scenarios and how your proposition would play out under them; what unplanned disruptors could get in the way, or how could your proposition done differently disrupt the market?

The experience engine

Enough of the customer and externalities, what will the proposition look like and why will the target customer go with it? There are three engines within the organisation that drive the proposition, the experience, delivery and value engines. So…

Utility

To be any good, the product has got to offer basic utility. It has to do what it says it is going to do. Sadly, too many products and customer propositions end there. A utility product will match the consumers needs. This is where most enterprise software sits…

- What are the key customer needs that the proposition must fulfil?

- What is the basic core functionality that must be met, what are the features that must be offered to gain traction in the market place?

- What features that are typical on competitor products that we could do without?

Quality

I could call this next box usability (as this follows the UXD model) but I think it goes beyond just usability. What is the quality of not only the immediate interface, but also with the supporting functions? For example, if you have a call centre to back up the proposition, how many layers of IVR are you forced through?

- Have you considered usability?

- Is the packaging aesthetically pleasing?

- The “happy path” customer journey may be well framed, but what about the “sad path”? What about when things go wrong, what about when customers don’t act in the way you expect of predict them to act?

Brand

It is easy to get carried away with a new idea before thinking about what it means to the brand. Typically there will be a strategic roadmap and whilst the proposition may be attractive it may not fit into where the brand is going.

- Is the proposition complementary to the overall brand direction or does it require a new brand and identity?

- Does the proposition support / leverage the brand?

- Does the brand already ‘do it’ under another guise (are you reinventing a wheel that has already been tried somewhere, sometime in the organisation’s history?)

- How will it be marketed?

Community

Finally, what is the ‘buzz’ that the proposition will create, what will get people talking and sharing it and how will you create this buzz.

- Is there a social network component built in that gets people talking and connected? How will it get people talking in external networks?

- What will cause people to recommend it to others?

- How can customers become part of its evolution?

- What of the proposition will get people passionate, what will drive them away?

Delivery engine

People

A successful proposition needs not only a talented, passionate and committed team to deliver it to market, it also needs a similar team to run it and support it when it is live. It is a common failing for a rogue “skunkworks” team to emerge in an organisation and develop what appears a compelling proposition, only to have it knocked back and closed down by the “Business as Usual” processes inherent in the organisation

- Who do you need to make the proposition successful? What is the team?

- Who will create the proposition and who will lead it? Is it IT led or business led?

- What are the cross-organisational boundaries that the proposition crosses and how will these be eliminated?

- Who will take ownership of the proposition once it crosses over into the market?

Process

- What are the processes that will be required to sustain the proposition?

- If the proposition will require changes to the organisation, how will they be managed, communicated and rolled out?

- How will the proposition be supported once it is let loose in the market?

- How will it be communicated to customers?

- How will you create new sales – sales force.

Technology

- What is the technology that will underpin the proposition?

- Is it possible to test the ideas using rapid languages such as Ruby on Rails before committing it to the enterprise Java stack?

- What integration is really necessary and what can be worked around?

- How can you deliver a beta version in the shortest period of time?

- How will you avoid heavyweight frameworks and develop incrementally to deliver value early and often?

- How performant and scalable must the innovation be?

Value Engine

At its most simplistic, how much will the proposition cost and how much revenue will it generate? Does it offer cost saving opportunities? Are there intangible benefits that will be accrued? Ultimately is it a viable proposition that is worth pursuing, or will the cost to develop and run outweigh the value it will add? Building out a financial model can take time, in the first instance this should be a napkin analysis, a wake-up call to make sure there is value in the proposition before too much time is invested in it.

Cost

Every day someone is working on the proposition it is costing you money. The quicker you can get something to market the faster you will start seeing a return on your investment, similarly the sooner you can “get something out there”, “test and learn” the sooner you can kill a proposition that does not fulfill its promise.

- How quickly can you get a beta to market?

- How many people, how many days?

- What will the cost be to develop the infrastructure?

- Do you have the skills in house or will you need to go external?

Benefit / Revenue

At its most crude, how will the proposition make money, but there may be more to what we wish to achieve. Is the proposition actually going to cut costs, a result of regulatory pressures or a CSR initiative?

What are the benefits that will be accrued – both tangible (e.g. financial) and intangible (e.g. social, environmental etc)

- If you are selling units are you going for high volume low margin or low volume high margin?

- If it an on-line proposition “advertising” is often seen as the source of revenue.

There are two additional components to the model…

Implementation

Having a compelling proposition is one thing, it is another to successfully communicate it and roll it out to target customers.

- In a crowded market place, how will the proposition stand out?

- What are the brand values it will communicate?

- What is the story that customers will hear and how will they hear that story?

- How will customers interact with the proposition, what channels will you use to take it to market?

- What is the roll out strategy?

Retain and grow

Winning customers is only the first step. A successful proposition will maintain a long-term relationship with its profitable customers, maintaining the warmth they have to the original proposition and cross-selling and up-selling new ones.

- How will you retain them and turn them into repeat customers and passionate advocates of the proposition?

- How will the proposition grow lifetime customer value?

- What can be cross-sold or up-sold?

- What can you bundle?

- How will the proposition deal with churn?

OK, so it’s not a perfect model and by no means complete. There’s some duplication in the thinking and many questions missing, but as any model it can be used to guide and prompt thinking and ensure there are no elephants left in the room when the first line of code gets cut. I’d welcome any comments on its usefulness, utility and direction.